Introduction

Every application has states. Whether we define them or not, we cannot escape from managing them, even if we are not fully aware of them. But the side effects of having undefined states are bloated databases and overly complicated logic. This complexity becomes increasingly difficult to deal with each time we need to change some logic, and our work becomes more stressful.

The purpose of this post is to present Finite State Machines (FSM) as a design pattern useful in managing the different states of a software application.

Those that have an engineering background, or simply like to create automation for fun, may already understand the FSM concept and its real-world applications. The concept of FSM in software development is analogous to how we describe different states that exist in the real world, although the input-output complexities of the virtual environment require different nomenclature than an analog environment.

Learning state machines is like learning a SUPERPOWER. Why? Because states are everywhere, and learning how to easily manage their complexity is a very powerful tool.

And what are these states that we are talking about?

Let’s consider the example of water. Water can exist in three different states: liquid state, solid state, gaseous state. External events, such as a temperature change, trigger a transition between these states.

Or, we can consider a lamp, with its On and Off states.

In each of these examples, we have mental models that allow us to describe the states of a current entity in an intuitive way. FSM allows us to do this with our applications.

But what are states in the context of software?

If you look at your codebase and see entities associated with columns like approved_at (or approved boolean column), pending_at, refunded_at, reproved_at, paused_at, failed_at, deposited_at , canceled_at, or even boolean-similiar columns, they are columns used to manage possible states that your entity can enter depending on certain conditions. Lets consider the following refund method:

class Transaction < ActiveRecord::Base # ...

def refund!

# check states one by one 😩

if pending_at.present? && canceled_at.blank? && deposited_at.blank? && refunded_at.blank?

update!(refunded_at: Time.zone.now)

else

raise 'Invalid state 🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥'

end

end

# ...

end

I’m sure that everyone who codes has seen a code like this. Maybe this code above doesn’t seem so bad to you, but think for a few seconds more and imagine having the ‘ifs’ for each of the states described above. Do we know exactly what state came before or after the current state? Or which actions to trigger before each state transition?

We probably would need to read a lot of methods and maybe walk through a few different classes to understand the context of the entity and its possible states. Only then would you be able to abstract what is going on (and even then, maybe not 😅).

Wouldn’t it be great to have a clear way of defining these states and managing them? The good news is that we can do that with Finite State Machines.

What is FSM in the context of software?

A state machine is a mathematical abstraction used to design algorithms that draw the state flow for an entity. The FSM is one of a finite number of states at any given time. A state machine reads an input (event) and switches to a different state based on the input. The FSM describes all the states, the transition between these states, the events that will trigger each transition, when a transition should happen (guard), and the actions to execute (like send and email, or call other method) once a transition is executed.

-

state: A description of the status of a system/entity in a given moment.

-

transition: A set of actions to be delivered when an event is received that will trigger a change from one state to another.

-

event: The “external” stimulus a system receives, often causing a change in its state. Once an event occurs, the system can either change, remain in its current state, and/or perform an action.

-

actions (callbacks): Any operation needed to ensure the expected behavior given a specific state. An action can start before or after a transition, or it can be triggered by an event.

-

guard conditionals: A condition that must be met for an event to trigger a transition.

Why should I use an FSM in my codebase if I can manage states with control flows?

The benefits of using a state machine in our codebase are:

-

Less cognitive load

-

Use of declarative programming: Focus on what needs to be done, not how to do it

-

Previsibility

-

Rules are well defined

-

No weird states since all states are defined. They name all possible states and define which the application should never enter.

State machines avoid situations where data silently becomes invalid. When used atomically with a database, we have security in state transitions.

Simply put, FSM makes it much easier to maintain and change the application states. Less time, less money, less effort.

Real Example:

Let’s solve a real software modeling problem that most fintechs encounter. We will use a Ruby state machines framework, AASM, although the state machine model can be applied to other languages. The solution will be divided into 3 steps, where each step presents a new scenario that demonstrates the ease and flexibility of state machines. We will focus only on modeling the problem, describing the states, and a few transitions between these states.

Step 1: Simple Deposit

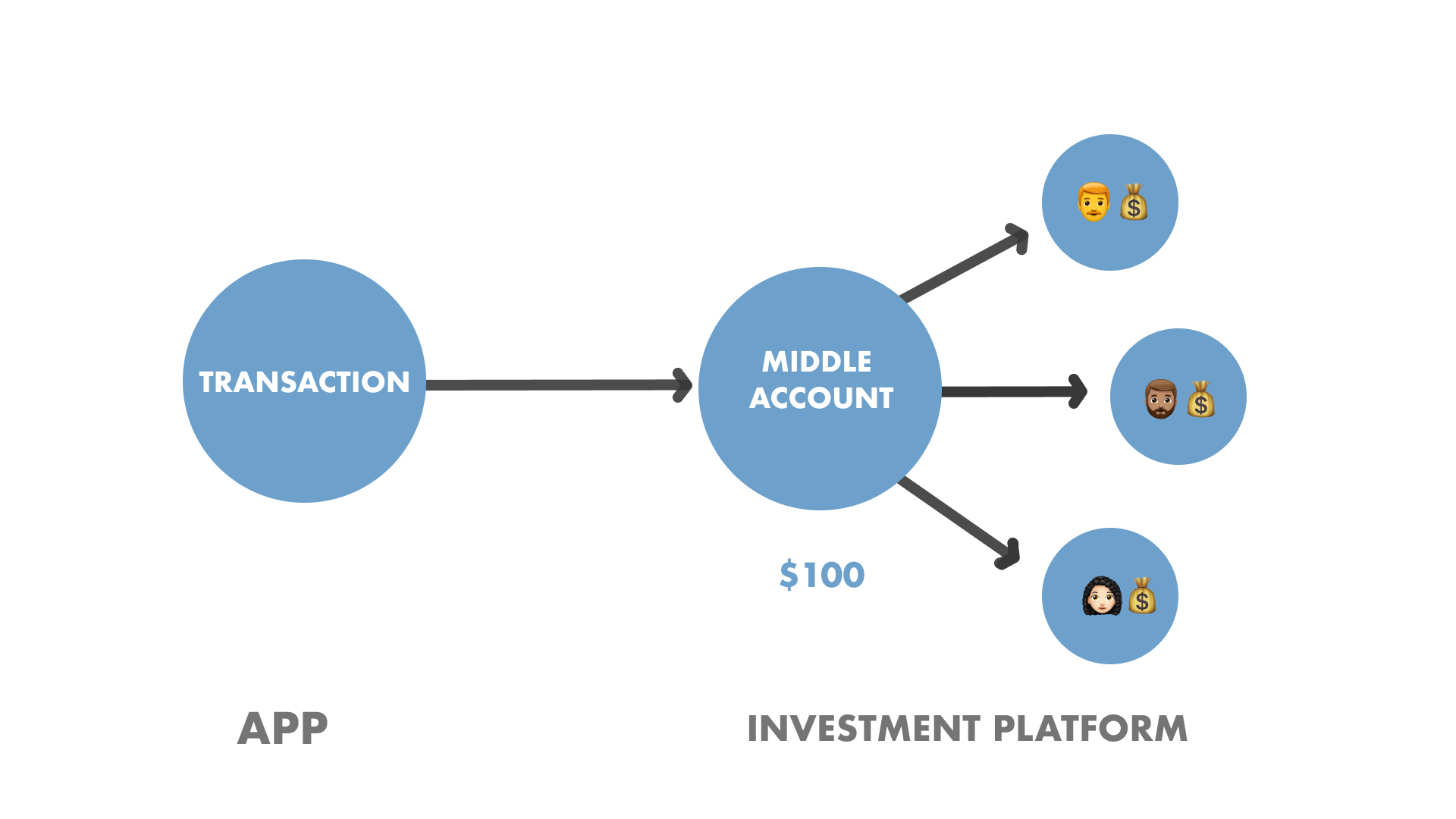

Consider a scenario where we have one Application with users’ accounts, and we’re asked to create a feature that invests the user’s local fund (‘App’) into an external investment account (‘Investment Platform’).

To model this problem, one of the solutions is to create a Transaction entity. We will have three states to represent each moment of this transaction.

-

draft: The initial state. This will be the state when a new record of the Transaction entity is created.

-

depositing: This state will represent a successful request to transfer money from the App to the Investment Platform. We need to have in mind that we are dealing with instantaneous transfers. A bank transaction can take a few bussiness days to be completed.

-

deposited: Once money hits the Investment Platform, we will use this state to represent that money has been deposited into the destination account.

module TransactionStateMachine # ...

end

class Transaction < ActiveRecord::Base

include TransactionStateMachine

end

Transaction.new

We would have an state machine similar to this one:

module TransactionStateMachine include AASM

aasm do

state :draft, initial: true

state :depositing

state :deposited

# events...

end

end

We declare all the possible transitions between states and which events will trigger the state transition:

module TransactionStateMachine include AASM

aasm do

state :draft, initial: true

state :depositing

state :deposited

event :depositing_via_api do

transitions from: :draft, to: :depositing

end

event :api_success do

transitions from: :depositing, to: :deposited,

after: [:update_balances]

end

private

def update_balances

# ...

end

end

end

The update_balances method is an ‘action’ that should be performed after the Transaction state transitions from depositing to deposited.

Step 2: Intermediary Account

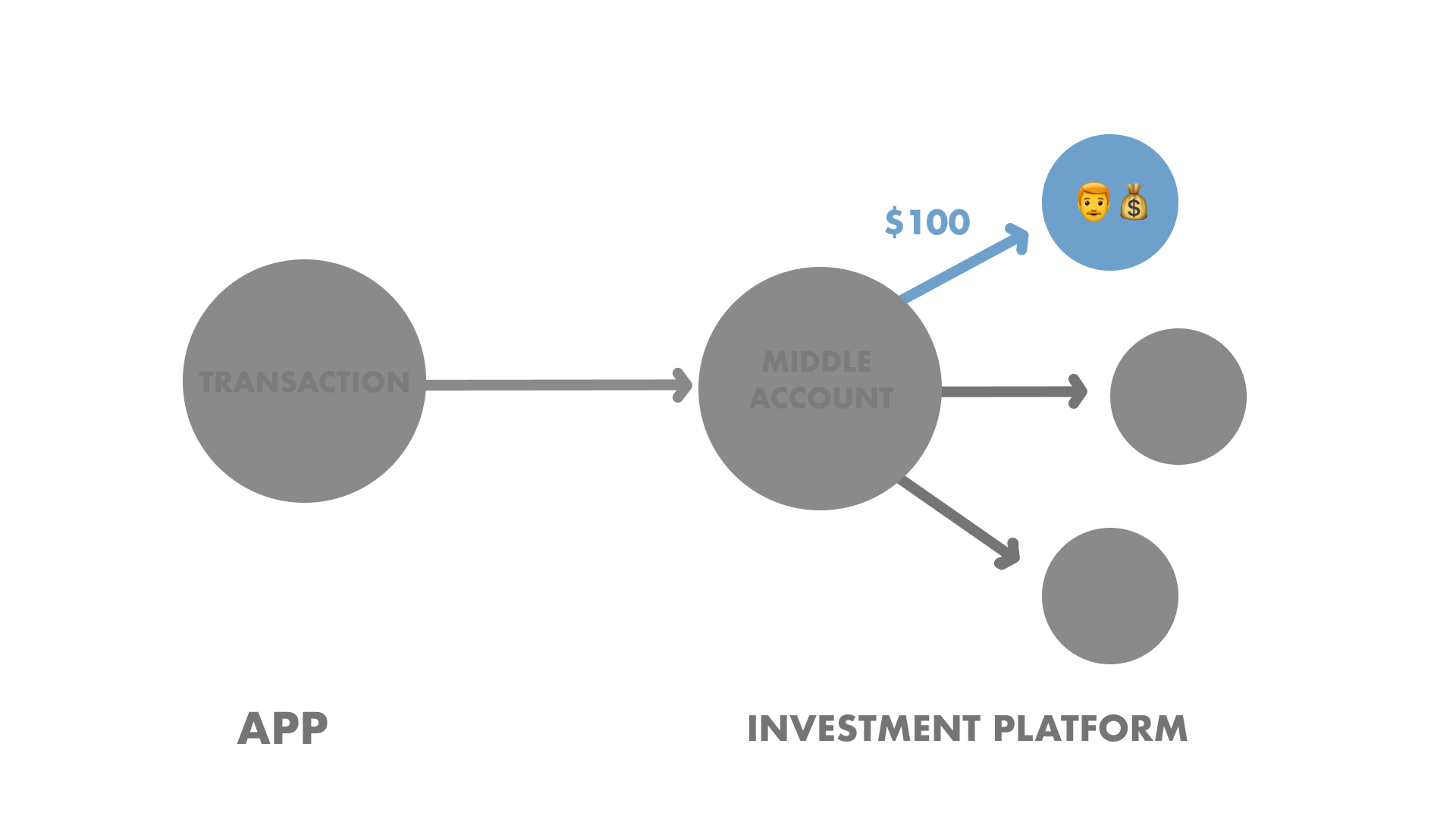

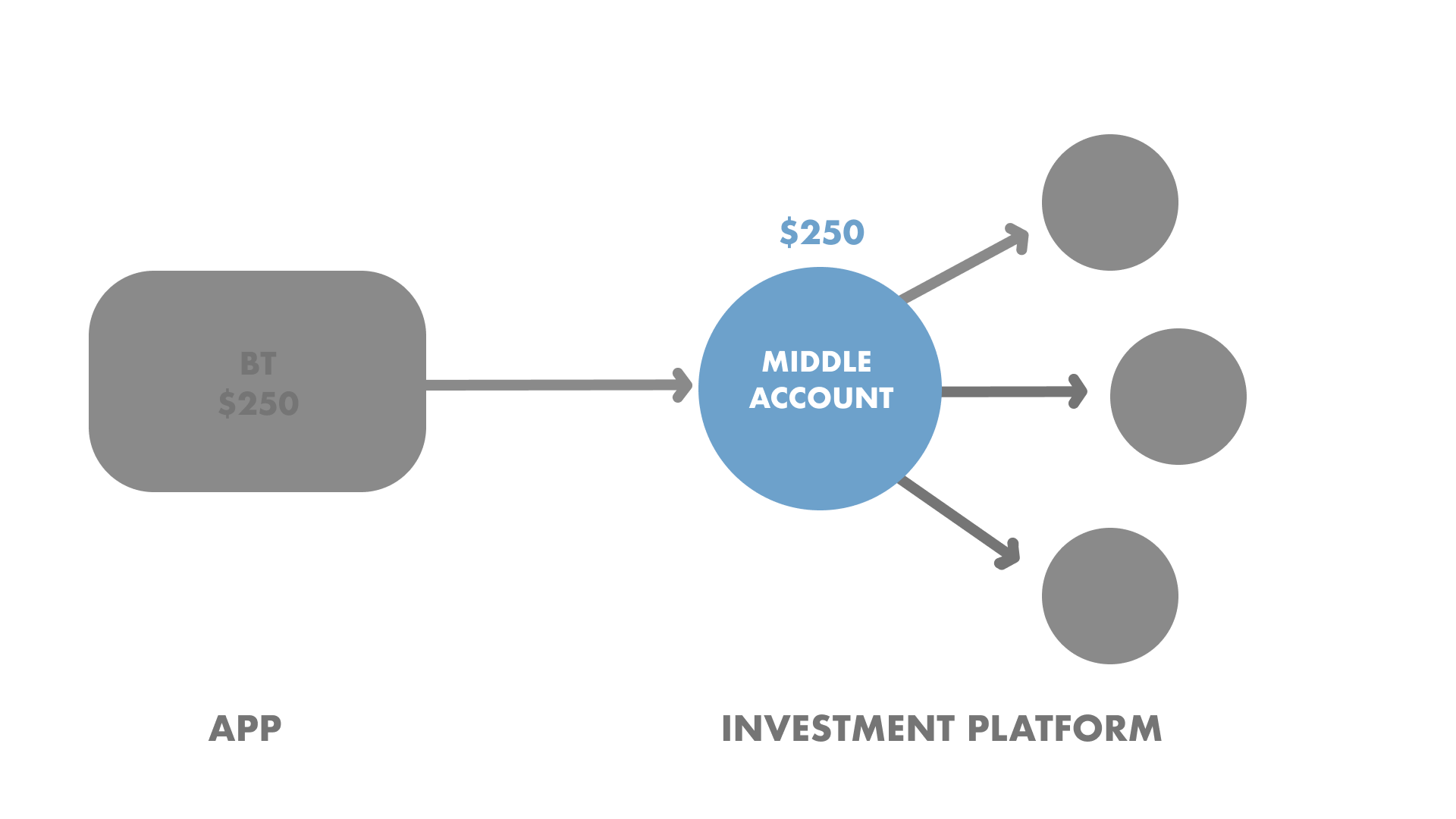

In another scenario, the transfer would not simply be from the origin account to the destination account, but from the origin account to an intermediary account (‘Middle Account’) on the Investment Platform. Then, once money is available on this Middle Account, we can request to allocate the amount to the destination account inside the Investment Platform.

What would be the change needed to implement this new criteria?

Since we have the Transaction state machine with the states and events in declarative programming, it is very simple to add new states to our entity. The flow from APP -> MIDDLE ACCOUNT is mostly the same as Step 1. The only thing that will change is that we need one more step until the money is available on the destination account inside Investment Platform.

As we can see in the image below, we need to represent the transfer from the MIDDLE ACCOUNT -> DESTINATION ACCOUNT in the Transaction state machine. To represent this in our state machine, we will add two new states:

-

invested: Once money hits the Investment Platform account, this state will represent that money is deposited in the destination account.

-

investing: This state will represent the successful request to transfer money from the MIDDLE ACCOUNT -> DESTINABLE ACCOUNT. Unlike the depositing state, this transfer is happening inside the Investment Plataform.

The same mental model we used to describe the problem above in words, we now use to describe the problem in code. This is because we are using a declarative programming format.

The same mental model we used to describe the problem above in words, we now use to describe the problem in code. This is because we are using a declarative programming format.

module TransactionStateMachine include AASM

aasm do

state :draft, initial: true

state :depositing

state :deposited

state :investing # <========== new

state :invested # <========== new

event :depositing_via_api do

# ...transitions

end

event :api_success do

# we added an after method on the transition from depositing -> deposited

transitions from: :depositing, to: :deposited, after: :start_next_transfer # <========== new

transitions from: :investing, to: :invested # <========== new

end

private

def start_next_transfer

StartTransferWorker.perform_async(self)

end

end

end

In addition to the two new states, notice that we have added an ‘after’ method to the transition from depositing -> deposited. And why is that? Well, with the new criteria of having an intermediary account, we need the transaction transitioned for all of the states to complete the transfer successfully: draft -> depositing -> deposited -> investing -> invested.

The after method start_next_transfer is added because once the state machine realizes that money is available on the MIDDLE ACCOUNT, we must initialize the next transition to complete the transaction flow. This is the reason for calling the start_next_transfer method after the transaction state transition from deposited -> deposited.

This is an example of FSM actions mentioned above. Since we have these callback (action) methods associated with the transitions between states, we can easily discover what actions must happen in each state that the application can enter.

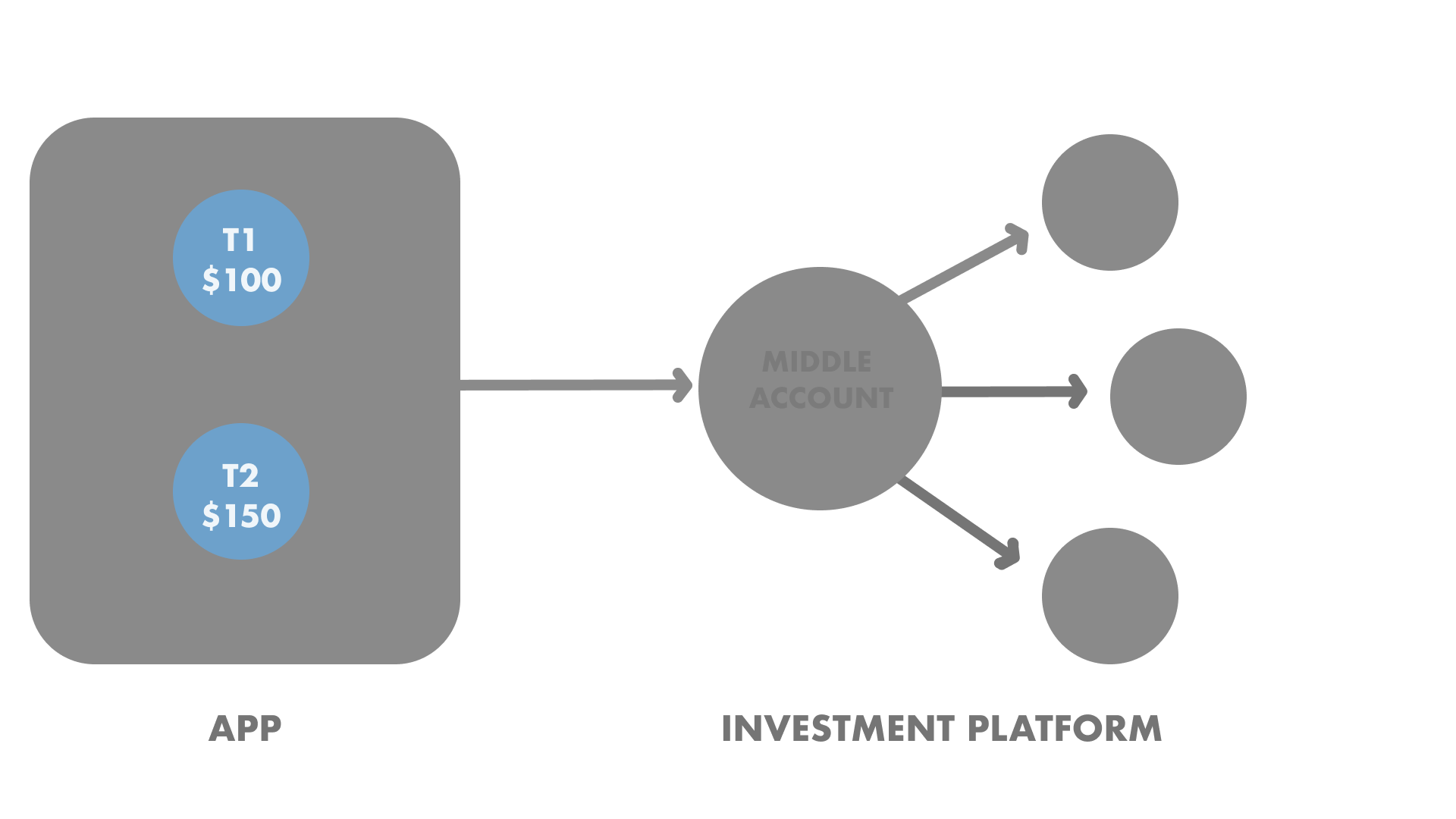

Step 3: Batch Transaction (Hierarchical FSM)

In a third scenario, we discover some very important information that obligates us to rethink how to represent the transfer between banks (transaction flow) in our codebase: Each transfer costs $0.20. This new information means that for 1MM transactions = $200,000 (💸💸💸💸).

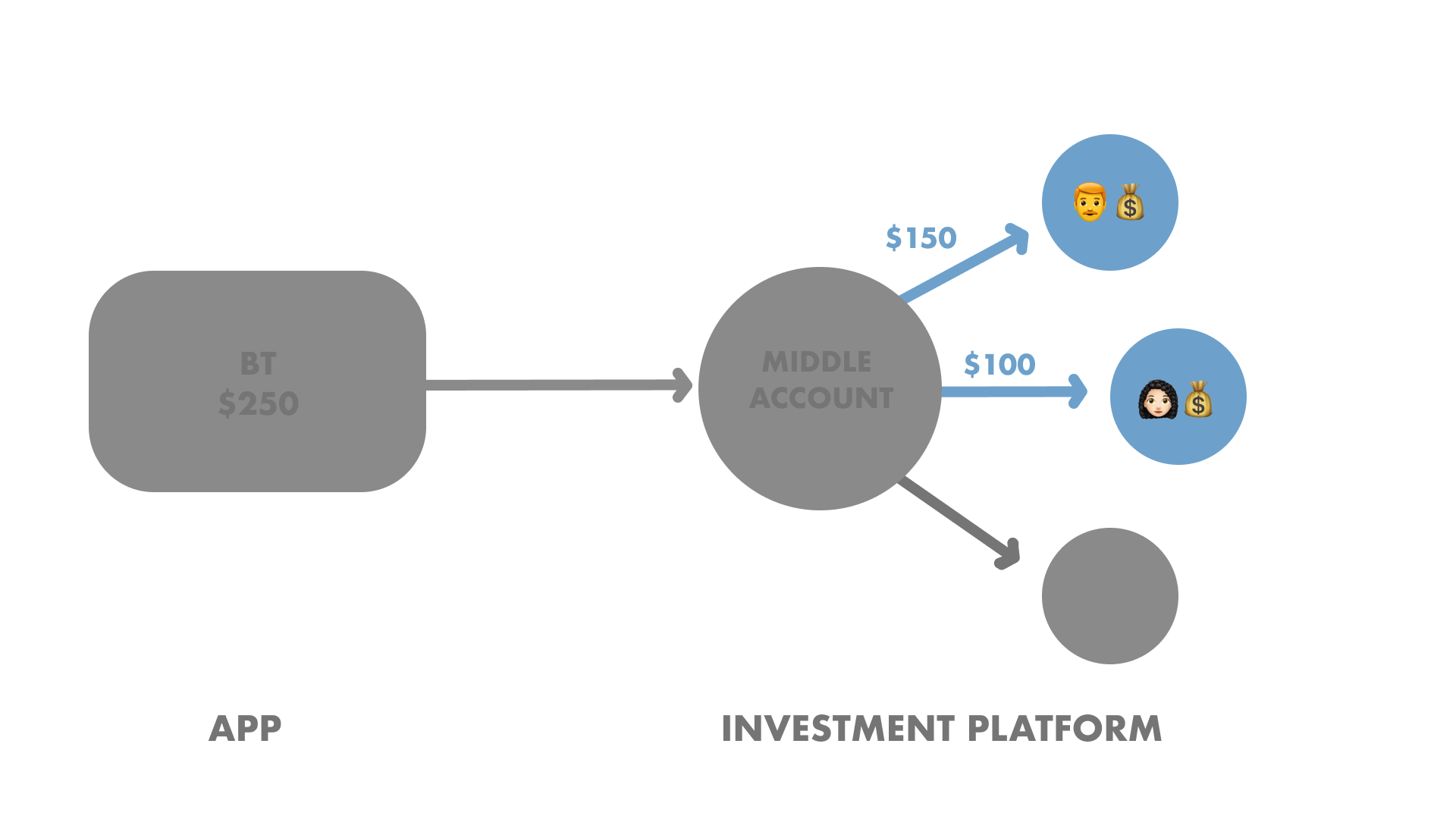

Let’s consider an example of two transactions, one of $100 and the other of $150 (as shown in the image below).

We have two main things that are represented by a

We have two main things that are represented by a transaction record that we show in Step 1 and 2:

-

the actual transfer between banks accounts (the APP bank account -> INVESTMENT PLATFORM Account)

-

the individual transfer created in our APP ($100 that a particular user wants to invest)

We used the same entity to represent both logics, but now we don’t want to use this entity to represent the transfer between banks because we will pay $0.20 for each transfer. We need to find a way of batching some transactions to minimize costs.

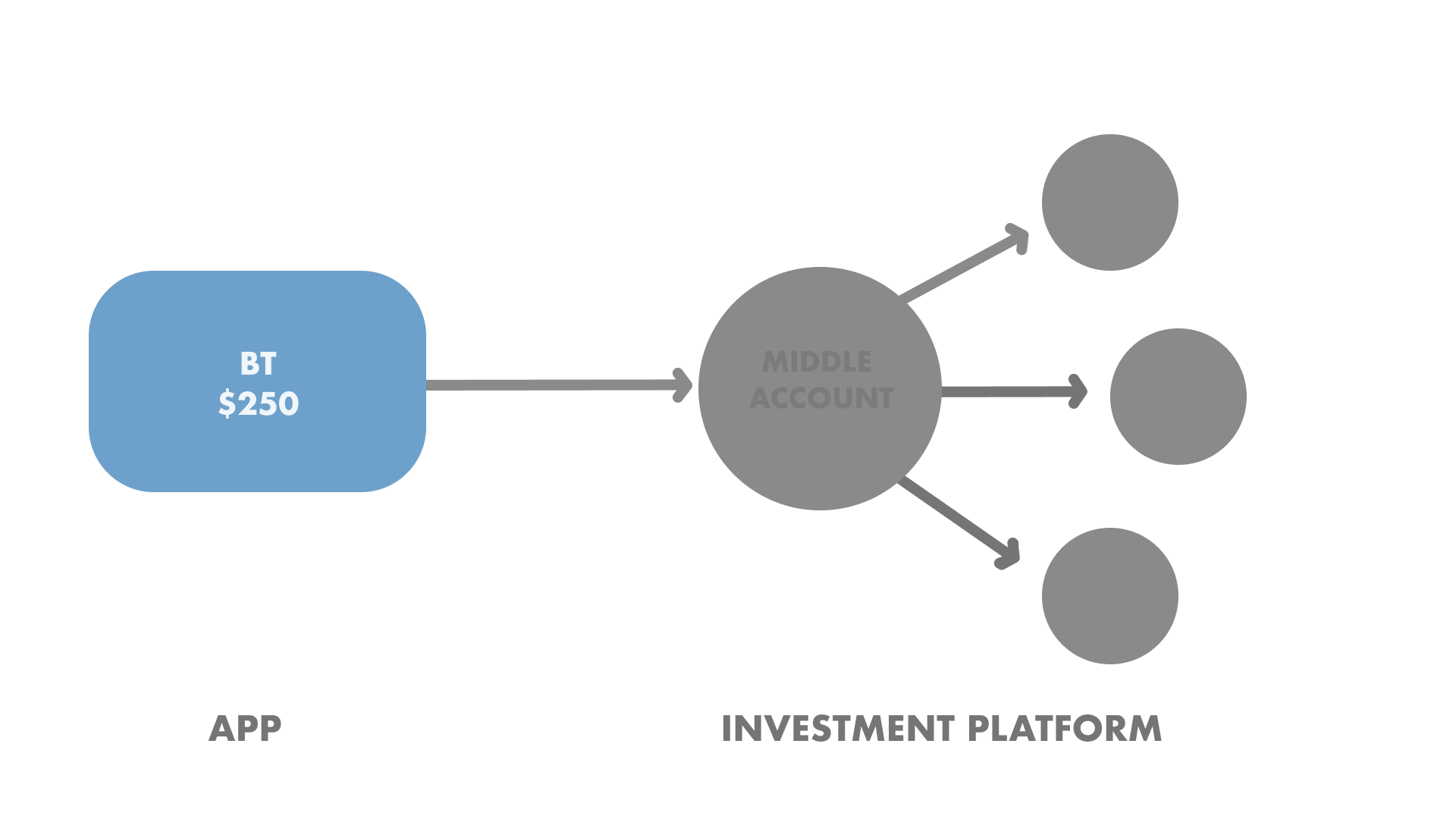

To batch transactions amounts, we will create a new entity called BankTransaction. This will be a relation of BankTransaction 1...n`` Transaction.

class BankTransaction < ActiveRecord::Base include BankTransactionStateMachine

has_many :transactions

end

class Transaction < ActiveRecord::Base

include TransactionStateMachine

belongs_to :bank_transaction

end

With this new entity, we can create a new bank transaction, and this record will have the sum of all associated transaction amounts. Considering the example above, we have two transactions: $100 and $150. Once we request to transfer money from one account to another, we will have a BankTransaction of $250 to represent this transfer between banks.

The Transaction State Machine will continue the same, but now the events on TransactionStateMachine will be triggered by actions on BankTransactionStateMachine.

This is how the

This is how the BankTransactionStateMachine would look - very similar to the Transaction state machine. Notice that the events on TransactionStateMachine will be triggered by actions on BankTransactionStateMachine. This is a case of a hierarchical state machine, since one state machine transition depends on another state machine.

module BankTransactionStateMachine include AASM

aasm do

state :draft, initial: true

state :creating

state :pending

state :settled

state :failed

event :created_via_api do

transitions from: :creating, to: :pending, after: :update_transactions_after_creation

end

event :settled_via_api do

transitions from: :pending, to: :settled, after: :update_transactions_after_settlement

end

private

# these actions calls the `transaction` state machine event

def update_transactions_after_creation

transactions.each(&:bank_transaction_created!)

end

def update_transactions_after_settlement

transactions.each(&:bank_transaction_suceeded!)

end

end

end

Once the total amount of transactions is available in the Investment Platform, we can request to transfer money to the destination accounts.

We can now split the amount and transfer the expected amounts to the users’ respective accounts. Since we are transferring money inside the Plataform, we do not pay any fee on these transfers.

The

The TransactionStateMachine is the same, we just changed the event names to a better reading.

module TransactionStateMachine include AASM

aasm do

# ...

event :bank_transaction_suceeded do

transitions from: :depositing, to: :deposited, after: :start_next_transfer

transitions from: :investing, to: :invested, after: :email_user

end

event :bank_transaction_created do

transitions from: :draft, to: :depositing

end

private

def start_next_transfer

StartTransferWorker.perform_async(self)

end

end

end

When should we use FSM in our codebase?

Should you use FSM when you have 1 or 2 or 3 states? Is it the quantity of states that determine when we should use FSM in our codebase? Or is it the complexity of each state?

The short answer, here, is that it’s not written in stone.

I have asked some experienced developers what their rules are for using an FSM approach. The answers are all different. The only thing that all of them agree on is that the more states or complexity between states, the more obvious the benefits of using a state machine becomes.

We are problem solvers and it’s up to us to decide when to use it. Some tips are, if you see the following things throughout the codebase, it would probably be beneficial to use a state machine instead:

-

Boolean columns in a database

-

Enums to model situations

-

Variables that have meaning only for some part of your application lifecycle

-

Looping through an if-else structure to check whether a particular flag or enum is set, and then execting actions based on that

My personal suggestion is:

-

If you are dealing with money, payments, bank transactions, and others: use an FSM approach. You only have to gain in these scenarios. Do not try to guess and think that your application will not change or grow the quantity and complexity of its states.

Conlusion

Finite State Machines can be used to model problems in many fields, including mathematics, artificial intelligence, games or automation. Finite State Machines come from a branch of computer science called “automata theory”. Its wide applicability, however, is only beginning to make its way into software applications.

The state machine model can be applied to many programming languages. You can even create your own state machine. FSM is used for modeling frontend and QA tasks too. In each case, there are gains from using FSM modeling. The main idea is to follow the modeling and logic of FSM, where we have all possible states defined, and we follow descriptive programming. These two main rules will give us the benefits of using FSM logic in our codebase.

With this new tool at your disposal, you will bring predictability to your codebase and regain some peace of mind when managing your application’s states.